Artist, writer, and arts consultant Neva Elliott introduces Midden, series of new and existing works in painting, print, sculpture, installation, and video projection by artists Sarah Edmondson, Mary Martin, and Niamh McGuinne, working collaboratively as the Midden Collective, and now showing at the Luan Gallery, Athlone. Enjoy a gallery of work by the Midden Collective above.

The trash heap has spoken

The case for pseudoscience and what we can learn from a pile of rubbish

When searching for answers, we look for evidence, the remains or trace of what has been and how it was; we look to what has been left behind. Midden (1) is an archaeological term for a pile of refuse, or a garbage heap in American parlance. Where there have been humans, middens are to be found — containing the broken and discarded remains of our lives and behaviours, our rubbish. Middens reflect our societies; both the historical treasures sought by archaeologists and the contents of modern landfills are a source of information about who we are and have been. There’s wisdom in them thar hills, or mounds of waste.

Perhaps it was an amateur archaeologist who came up with the character of Marjory the Trash Heap in Fraggle Rock (2). Marjory is an animate midden. Revered as a wise oracle by the Fraggles and tended to by her rodent aides, Philo and Gunge, who herald, “You are in the presence of the all-knowing Trash Heap! Nyaaaah!” (The Fraggles address her by more formal titles of “Madame Trash Heap,” “Madame Heap,” and “Your Trashiness”.) In the words of Philo and Gunge, Marjory “knows all” and “tells all.” In Marjory’s terms, “the Trash heap is all,” “I’m orange peels, I’m coffee grounds, I’m wisdom!” referring to her role as the rubbish dump or compost heap of the Gorgs (giant squishy humanoid characters). Marjory has the guidance the Fraggle seek, in the form of mottos and practical instruction (usually put to song); “always wear your hat”, “Don’t be alone. Get some friends. Friends help,” and sometimes mystical objects such as a lucky blanket or love potion.

Marjory’s gender is no accident, referencing matriarchs as a reliquary of familial domestic and alternative knowledge. Such gendering invites discussion about how lived experience, unconventional approaches to understanding, and other ways of knowing are deemed female domains. One of the reasons alternative wisdom appeals to women is the failure of science to properly study and treat women and women’s bodies or even listen to them. Historically women have been inequitably treated by science, not just as practitioners but excluding them from medical research (3). Such gender bias threatens the validity of scientific findings; for example, one cannot assume that conclusions from scientific research undertaken on men would apply to females, as drugs may have different effects on men’s and woman’s bodies (4). And where we have had gender-specific treatments, they have a long history of stigmatising beliefs about women’s bodies; for example, menstruation has been seen as unclean, and don’t get me started on wandering uteruses and hysteria.

(Biology differs not only between men and women but also among racial and ethnic groups; an understanding that comes only after decades of data gathered primarily from men of European descent.)

Even if we take clinical findings, the science, as being sound being listened to also matters. Female patients are more likely to be ignored or considered as overreacting when they try to talk about their health (5). So normalised is this in the medical profession that the term ‘Yentl Syndrome’ (6) was coined to describe the negative gender bias in treating women after heart attacks.

Systemic problems with conventional science leave women understandably searching for answers in other places –folk culture, oral traditions, superstition, ‘old wives tales,’ personal beliefs and magical thinking. These pseudo-sciences are a way to sidestep scientific authority and find forms of knowledge beyond what it has to offer.

Artists also question through alternative means and eschew authority. We enquire and probe, defy laws and sciences to push beyond the known and accepted; we find other ways to not only answer but also question.

‘Péarla’, ‘Daow-sa’, ‘Ban-sheedah’, 2021/22

Midden Collective are Sarah Edmondson, Mary Martin and Niamh McGuinne.

Edmondson, Martin, and McGuinne’s work takes the stuff of the institutional sciences; ecology, biology, cosmology, and geology and combines it with the supernatural, speculative fiction and pseudoscience to move into metaphysics and epistemology through investigating and challenging the creation of knowledge. A hyphenated real-unreal, using the structures that tell us what we know about ourselves and the universe to poke at other potential realities.

Airdeogaí, Gwee, Ban-sheedah, Lan-gone, Mary Martin’s titles sound ancient, dug out of the earth, a language spoken by Sheela-na-gig and púca. Indeed they may be; titles Ring-ka and Daow-so are phonetic for the modern Irish words for dance, ‘rince’ and ‘damhsa,’ her use of the sounds of words pointing back beyond language as we know it to something more primitive. Backwards – forwards.

In Martin’s acrylic on canvas paintings, fish loom out of barren landscapes and dance with strange figures with nondescript bodies and mask-like faces – gasmasks, tribal masks, astronaut helmets. Fish crawled out of the sea about 375 million years ago and developed the physical characteristics to survive on land, evolving to walk, to dance. We are the evolution of these fish out of water. Who are the aliens with their hoods and breathing apparatus in this strange landscape? Are they aliens of the extra-terrestrial kind, or are these flailing bodies foretelling our evolution, transformed to deal with thinning air, or encased in technological suits so we can survive in harsh future landscapes? On an earth of muted tones of mud and sand speaking to a future changed; where climate disaster has played out, and here we are, or are not, in this post Anthropocene doomscape.

Dancing together in Mary’s future vision is the fantastical past we have learned to accept in biological evolution and a potential future that seems equally incredible; a world where a form of progression in response to the climate has taken place. The fish and the alien dancing their salutary tale – if it could happen to a fish, it could happen to you. But, of course, maybe it’s not us at all, perhaps we have left the picture, and this is some new anthropomorphic creature, risen out of the gunge.

The organisms rising from the surface of Sarah Edmondson’s moon are worms, moonworms, who feed on moon soil and cast moonworm middens. Edmondson’s ‘Arenicola Luna’ is a phantastic research programme into these posed lunar invertebrates. It is a construct to speak about learning, how we create knowledge, and who its arbiters are. Edmondson’s installation commandeers scientific research and institutional educative practice modes to develop a series of projection apparatuses and installation/sculptural pieces. This modal hijacking acts as a comment on and challenge to these accepted structures, their inadequacies, corruptions, and human centricity.

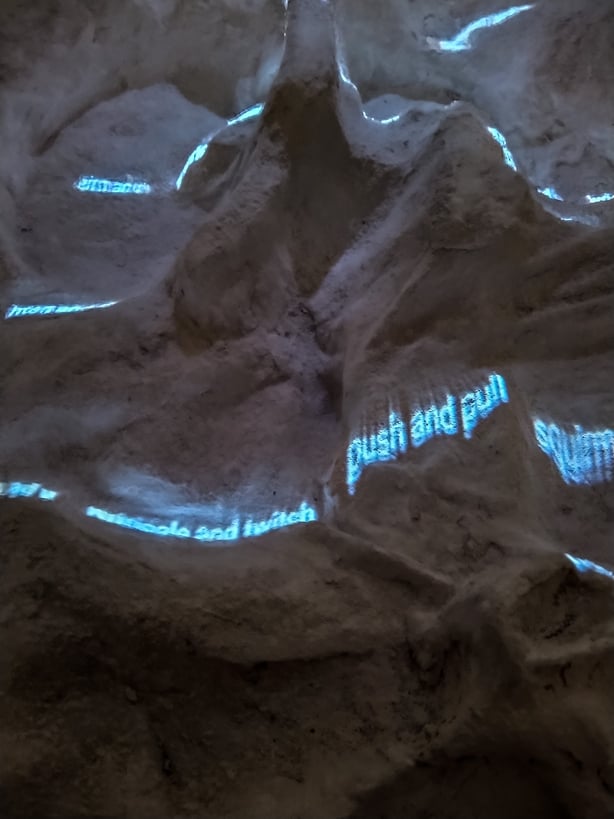

‘Wormhole’, a moving image projection tunnel, depicts the moonworms (in actuality, artificial worms mimicking the movement of real worms) in their underground habitats. The set of ‘Proto-Midden’ shows worms excreting lunar soil, suggesting how lunar middens might have formed. In ‘To Wormate’, words describing the movement of the moonworms scroll across a diorama of the moon. However, these words are in Tlön, the fictive language of Jorge Luis Borges, and exclude nouns. Tlön, an imaginary geographical and cultural place invented through language offers a way into Edmondson’s work. Finally, ‘Totally Telescopic’, a moving image back projection of the moon, works to include the viewer in the piece. Its imagery moves from the moon at a distance to closeups of moonworms to YouTube clips of people identifying moon tunnels on earlier Google Earth documents (now unavailable or ‘hidden’). Here we, the viewers, are part of the physical piece and the truth or untruth of this moon story.

Edmondson’s narrative construct places her at the origin of knowledge and challenges its very nature. To know something is to capture it, not just as knowledge acquisition but as a pinning down, a possession and proto-ownership. In previous work, she re-cast the basic unit for measuring distance as a squirm, based on the length of a worm. While fictional, she has given it a rational basis – “speed is calculated by dividing the distance travelled by the amount of time passed. Time is variable. It depends on the location and how good of a time the worm is having. The velocity is always zero.” That these moonworms “may or may not have existed” and “might or might not evolve” is of no consequence to Edmondson. Scientific realism is no barrier to acquiring knowledge; there are still truths to be found, some of them by closely studying fictitious moonworm poo.

In the river gallery, a giant sculpted ‘mother-shell’ hangs over a cluster of empty oyster shells. Failed protection; her flock consumed, their hearts are eaten out. We have come to the aftermath of Niamh McGuinne’s bivalve massacre. We do not know if this mother has been devoured too, or if she fled the scene; in ‘A Fragile Armour’, we can only witness her carcass slowly turning above those of her diminutive charges, amassed on the floor, mounded as rubbish. Here the discarded midden, its life shucked out.

Facing this tableau are the gallery windows, covered with a printed film (screen print on polyester), depicting the oyster shell’s barnacled exteriors backed by a grid. The image reminds me of cyanotype, one of the oldest forms of photographic printing, which results from exposure to ultraviolet light, traditionally used to reproduce technical drawings as blueprints (until the arrival of photocopy machines). The population of deceased oysters has been mapped, examined and contained for posterity.

‘Creatures of Love’, three photo-intaglio prints on paper, follow on from the riverside windows. Here the shells are shown individually, closeup bounded by graph paper, one hand drawn. Each exoskeleton is scrutinised for what we can learn from their smooth valleys and craggy ranges, alluding to archaeological and geological research.

Near ‘Creatures of Love’, positioned on the floor, is ‘Mound’, a literal mound, here of photocopies and chine colle prints from ‘Creatures of Love’, which the artist coated in encaustic medium and shaped over her hand — seeming to devalue the images by taking them down from the wall, photocopying, and sweeping them up in a mound. Though including the chine colle prints retains something of traditional ‘value’ in this depreciation.

McGuinne’s works bring us through the learning process – from the originating midden as a research site, dissected into pored over individual fragments, before being understood and interpreted into common knowledge passed through many hands. A move from rubbish to near fetish and back through time, though a pearl of worth always remains. This passing of time is doubly reflected in how each oyster shell is created – its strata a build-up of calcium. Something McGuinne links to calcifications in us humans, caused by infection, trauma, tumours, and heart disease.

This brings us to ‘Folly’, her latest work, where she takes us inside the artefact. ‘Folly’ is an aluminium box printed with the pattern of oyster shells, with a silver foil mirrored interior. Here the artist is trying to suggest being inside the oyster shell, the oyster has gone, and we are now the occupant. We, too, will someday be husks for the study.

The trash heap has spoken.

Midden is at Luan Gallery, Athlone until 20th November 2022 – find out more here.

REFERENCES

(1) The definition that the Midden Collective use is –

1: DUNGHILL

2a: a refuse heap: KITCHEN MIDDEN, Shell Midden (archaeological)

2b: a small pile (as of seeds, bones, or leaves) gathered by a rodent (such as a pack rat)

(2) Fraggle Rock is a television series about muppet creatures, created by Jim Henson.

(3) There is well-documented bias in health sciences research; females were excluded from most biomedical research based on scientists’ belief that female hormonal release made them too variable to study. Drug trials with US government funding only started including women in the 90s, meaning many generic drugs may not have been investigated in women.

(4) For example, aspirin has been a well-accepted agent for preventing a heart attacks in men. Still, a 2015 study found that taking a low dose of aspirin every other day is ineffective or harmful for most women in preventing heart disease.

(5) A 2018 study found doctors often view men with chronic pain as brave or stoic, but women with chronic pain as emotional or hysterical. A survey conducted in 2019 found that one in five women say they have felt that a health care provider has ignored or dismissed their symptoms.

(6) “Yentl Syndrome” is named after the play/film in which a woman poses as a man to gain an education. Yentl Syndrome was coined to highlight that women die after heart attacks more often than men because of inadequate treatment.